The 222-mile Colorado Midland Railway ran between Colorado Springs and Aspen via Leadville, providing access to remote mining areas. The train also offered tourist excursions, often highlighting wildflowers along the route. Completed in 20 months, it was the first train to use standard-gauge rails over the Continental Divide in Colorado’s Rocky Mountains.

Passenger service began in July 1887, between Colorado Springs and Buena Vista. At the end of August, 15 days earlier than expected, service was extended west to Leadville. This segment included thirteen bridges. West of Leadville, the train traveled through the 2,161-foot-long Hagerman Tunnel, crossing the Continental Divide, then the highest railroad tunnel in the world. On February 4, 1888, regular train service continued on to Aspen. The train provided a convenient route for passengers traveling to and from the Aspen mining district and, most importantly, it provided an economical way to transport ore to its marketplace.

But the high-elevation route was plagued by snowstorms. During the first four months of 1899, the train was inoperable for seventy-seven days due to snow. These costly delays forced the company to travel through a lower-elevation tunnel, the Busk-Ivanhoe Tunnel. In September 1890, with mounting debt, the railroad was sold to the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway, and its name was changed to Colorado Midland Railroad.

After several mergers, the Colorado Midland Railroad Company was legally dissolved on May 21, 1922.

Many photographers documented the Colorado Midland, including William Henry Jackson, Louis Charles McLure, and Harry Hale Buckwalter. This blog post will discuss the work of photographers J. L. Clinton and W. Ira Rudy, who photographed the railway in the late 1880s. They worked both in partnership and alone.

The Photographers

James Luman Clinton was born on June 15, 1860, in Clintonville, Wisconsin, to Luman W. Clinton and Sarah Ann Sharp Clinton. When President Lincoln called for an additional 300,000 men to serve with Union troops in the Civil War, Luman Clinton volunteered with the 21st Wisconsin Infantry. In September 1862, he mustered into service, leaving his pregnant wife and three children behind. A month later, he died on the battlefield at Perryville, Kentucky.

The eight-dollar monthly pension Mrs. Clinton received was not enough to support her family. She operated a millinery shop until 1880, when the family moved to Madison, Wisconsin, which offered her children more educational opportunities. The city provided many job opportunities for the Clinton children. Eva, the oldest child, was employed as a seamstress, James worked in a printing office, while his younger sister, Lulu, retouched negatives at Andrew Isaacs’ photo studio. A year later, she died tragically in a boating accident.

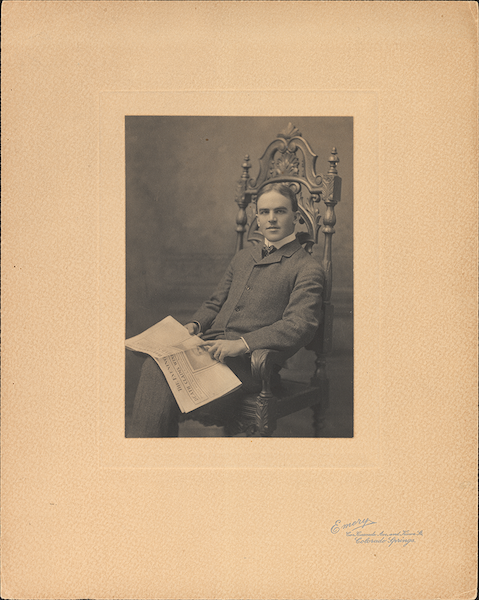

In 1885, Isaac hired James as a photographer. The following year, James briefly worked in Cottonwood Falls, Kansas, before moving to Colorado Springs, Colorado, where his photographic career flourished. Clinton took over Franklin A. Nims’ studio at 18 South Tejon Street. He married his Wisconsin girlfriend, Emily Dodge Prescott, on May 5, 1887, in Colorado Springs. The couple was very active in the Baptist church.

In 1889, Clinton partnered with W. I. Rudy. They served as the official photographers for the Colorado Midland Railway. In 1891, Clinton signed a five-year lease for a new ground-floor photography studio in Colorado Springs. In 1893, he traveled west to Glenwood Springs and later east to Elbert, Colorado, making portraits, scenic views, and views of residential buildings.

By 1896, Clinton seems to have abandoned photography and invested in a new mining venture. A few years later, he owned a peach orchard in Palisade, Colorado. He expanded his farm to include cherries, potatoes, and alfalfa.

Mr. and Mrs. James L. Clinton died of pneumonia within three days of each other in January 1930. The couple was laid to rest at the Palisade Cemetery. They were survived by Mr. Clinton’s 94-year-old mother and their son and his family.

William Ira Rudy was the second child of Isaac and Sarah Ann Groff Rudy. He was born around 1855 in Stark County, Ohio. His father was a merchant in the dry goods business. By 1860, the family was living in Mendota, Illinois. In 1867, when Ira was about twelve years old, the family settled in Olathe, Kansas.

In August 1876, Ira and his older brother Dan opened a music, book, and stationery store in Abilene, Kansas. They sold Steinway & Sons pianos, sheet music, pens and paper, and even sewing machines. In February 1877, the brothers sold their interest in the business to their partner, B. F. Maxwell. In 1880, Ira moved 12 miles east to Chapman, Kansas, where he worked in a drugstore and taught a band music class.

On August 8, 1881, Rudy married Anna Rohrer in Chapman, Kansas. The following February, Ira and his brother, Dan, left Kansas and headed west. By June of that year, Ira’s wife had joined him in Colorado Springs, where they settled in Colorado. By July 1883, Ira had set up a “museum” filled with a “collection of odd and beautiful things, a capable taxidermist, who mounts or stuffs birds, skins of animals, in the best style; and a complete museum department, consisting of sheet and book music, violins, accordions, banjos, guitars, &c.”

Rudy employed people who traveled to Mexico and New Mexico to acquire Native American artifacts for the store. They brought back beads, blankets, pottery, and moccasins. Tourists could purchase items and have them shipped anywhere in the United States. A room in the back of the store housed live birds and animals, including a young antelope and a Golden Eagle.

By 1886, Ira’s younger brother Frank had moved to Colorado Springs, where he worked as a painter and paperhanger, while Ira pursued scenic photography, a field he would work in through 1894. In 1889, Clinton partnered with W. I. Rudy. During this period, he documented the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway and the Colorado Midland Railway. His work was published in the Midland’s circulars and publicity materials.

In 1896, Ira Rudy established a mining company with a group of Colorado Springs residents. This business was likely unsuccessful, as by 1900, Ira left his wife and young daughter and moved to Seattle, Washington. A few years later, he worked as a bartender in Los Angeles. In 1907, Anna obtained a divorce from Ira on the grounds of desertion. Ira Rudy appears in the 1910 federal census as a hotel clerk. I have not found any further information about him.

Thank you to History Colorado staff, and to Hillary Mannion, Archivist, Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum.